Let’s assume you’ve got all of the boat safety equipment basics covered: good quality PFDs for everybody on board, your required Type IV throwable PFD(s), fire extinguisher(s), a full complement of pyrotechnic distress signals, and a functional emergency cutoff switch with a lanyard worn by the operator.

That’s a great start and enough to avoid a citation if you’re inspected. But your goal in outfitting your boat with safety equipment should be keeping you and your crew safe, not just complying with the law. What additional safety equipment you’ll need depends on how and where you use your boat.

Beyond the Requirements

On almost any boat, required safety gear should be just the beginning. Beyond that, the type of safety equipment you choose to carry should depend on a number of factors: the characteristics of your boat, the experience level of your crew, the climate in your home region, how readily available help is likely to be and many others. Ultimately, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all formula or checklist; it comes down to understanding the risks involved in your own type of boating and making informed decisions about how to address them.

For the purposes of this article, we’ve tried to break down boat safety equipment into a few categories: legally required, must-have, should-have, and nice-to-have. These aren’t universal, of course. For example, for a wakeboard board used exclusively on lakes in the inland South, a life raft is a waste of money and space. For a sportfisher routinely used for multi-day trips to the Atlantic canyons, it’s almost a must-have. That said, these lists should at least get you started thinking about your own specific safety gear needs.

Must-Have Boat Safety Equipment

This is the safety gear that — with a few exceptions — every boat should have. None of it is required by law or regulation, but all of it is required by common sense.

Anchor(s)

An anchor isn’t just a convenience item; it’s also a vital piece of safety equipment that can keep you from drifting onto a dangerous downwind or downstream shore in the event of engine trouble.

Make sure to get one well-suited for your boat and home waters, and don’t skimp on the rode.

Electric bilge pump(s)

An electric bilge pump won’t keep you from sinking if you put a significant hole in the bottom of your boat, but it’s effective at pumping out water from waves coming over the bow or sides, heavy rainfall and small leaks in below-waterline plumbing. In small, simple boats with no deck — aluminum jon boats, for example — a bailing bucket is a decent substitute, but for the most part all powerboats should have functional bilge pumps.

Bailing bucket or manual bilge pump

“The best bilge pump in the world,” the old saying goes, “is a scared man with a five-gallon bucket.” In the event your electric pump fails — which isn’t rare — you’ll need some other way of getting water out of the boat. Buckets — especially square buckets like those cat litter is sold in — are fast for getting water off the deck but usually won’t work to get it out of the bilge. A manual bilge pump is needed for that.

Buckets — especially square buckets like those cat litter is sold in — are fast for getting water off the deck but usually won’t work to get it out of the bilge.

VHF radio

EPIRBs and PLBs are great, but if you boat in areas with significant boat traffic, the fact is that a VHF radio, used correctly, will usually get you help faster since you can likely reach nearby boaters. Throughout most of the U.S. and U.S. territories, you can also contact the Coast Guard from anywhere within about 20 nautical miles of the coastline, even with a handheld radio transmitting on low power

A fixed-mount radio with a 3-dB or 6-dB antenna has more range than a handheld, but a waterproof handheld has the advantage that you can take it with you if you have to abandon ship. Obviously, the importance of a VHF radio as a safety measure depends on where you’re boating. On a mountain lake in the West, a cell phone will likely be a better way to call for help; on coastal waters, a VHF is better.

GPS

A GPS serves a couple of key safety functions on a boat. First, it obviously helps you navigate safely. Second, it tells you precisely where you are at the moment so you can communicate that information to responders in the event of an emergency.

A GPS tells you precisely where you are at the moment so you can communicate that information to responders in the event of an emergency.

Many modern VHF radios can digitally embed your coordinates into a distress call, but it’s important to also be able to see and verbally communicate your coordinates. Make sure you know how to quickly display your current position on your GPS unit. As with a VHF radio, the importance of a GPS as a safety measure depends on where you’re boating.

First-aid kit

Carrying a first-aid kit is a no-brainer. Figuring out what it should contain takes more thought. Of course you’ll want the usual band-aids, gauze pads, antiseptics, ointments and so on, but if you’re going offshore, where additional supplies might be hours away, consider more. For example, you’ll want prescription/rescue medications for any of your crew who use them, seasickness medication, side-cutter pliers for cutting hooks, wound closure strips, a space blanket and so on. If anyone in your crew has medical training, consider suturing supplies.

Serrated knife

Getting a propeller entangled in rope — such as a lobster or crab trap float line — can be a serious safety issue, especially on a single-engine boat.

A stout, serrated boating knife meant specifically for cutting rope can get you underway again, especially if you also keep a dive mask aboard.

A good knife can also be a lifesaver if something goes wrong while towing or being towed, while rafted up with another boat or in the event of a fouled anchor in bad conditions.

Should-Have Boat Safety Equipment

The “should-have” list includes safety gear that’s less critical than the “must-have” items, at least for most kinds of recreational boating. This gear essentially builds onto the must-have gear, increasing your margin of safety on the water. Most of it, though, is more important for boaters who venture offshore.

EPIRB and/or PLB

While a VHF radio is a more essential — and more affordable — piece of boat safety equipment than a satellite locator beacon, EPIRBs (emergency position indicating radio beacons) and PLBs (personal locator beacons) have capabilities radios don’t. First, they can transmit your distress signal and location from anywhere on the planet, so proximity to another boat or a Coast Guard shore antenna isn’t an issue. Second, they’re waterproof and float, which isn’t true of many VHF radios. If you routinely go more than 20 miles offshore or travel outside U.S. waters, you need a satellite locator beacon.

Wireless engine cutoff device

On virtually any powerboat under 26 feet, the operator is required to use an emergency cutoff switch, but the fact is that clipping a kill switch lanyard to yourself is enough of a pain that many operators don’t do it.

A wireless kill switch allows the operator to move freely around the boat but still kills the engine(s) if they go overboard. If you often boat by yourself and don’t religiously wear your kill switch lanyard, this becomes a must-have.

Waterproof VHF radio

Assuming your primary VHF radio is a fixed-mount unit, a backup handheld unit provides important redundancy. If the electrical system on your boat goes down due to flooding, fire or another issue, your fixed-mount VHF is worthless.

Even a small issue like a failed connection in an antenna cable can disable your primary VHF

Even a small issue like a failed connection in an antenna cable can disable your primary VHF. A handheld backup, though, is completely self-contained. Choose a waterproof — and, better yet, floating — model and you can take it with you if you have to abandon ship. That allows you to stay in real-time contact with rescuers.

Redundant electric bilge pumps

Breakers trip, fuses blow, pumps burn out, hoses split and hose clamps fail. When any of those things happens, a backup bilge pump can save your boat and possibly your life. Ideally, secondary pumps should be wired on a completely separate circuit and plumbed with a completely separate discharge hose and through-hull so that a single wiring or plumbing issue can’t disable both pumps.

A backup bilge pump can save your boat and possibly your life.

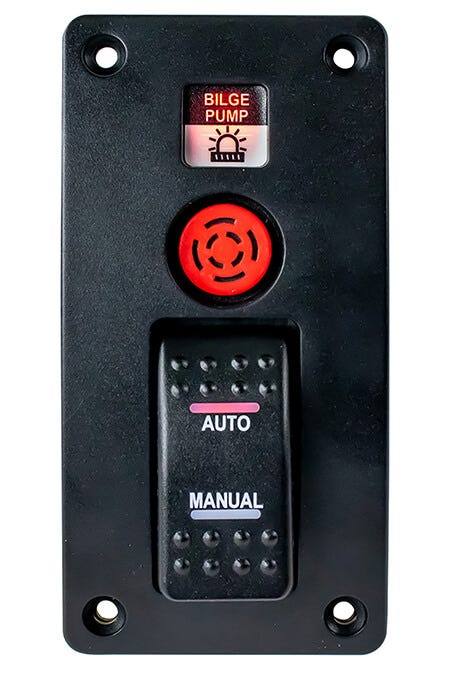

Bilge alarm

Here’s the scenario: you’re cruising out to the Gulf Stream 40 miles offshore, and unbeknownst to you, water is pouring into your bilge through a crack in a below-deck livewell hose. But your bilge pump — equipped with an automatic float switch — is able to almost keep up with the leak, so you’re not even aware that your bilge is gradually flooding.

Eventually, though, your pump will get behind, something in your electrical system will short, and you’ll be in real trouble.

A bilge alarm keeps this from happening by alerting you every time your bilge pump turns on so you know if something is amiss. A variety of purpose built bilge operation indicators and high-water alarms are available, but you can also simply wire a small red light or an audible buzzer into your existing bilge pump circuit.

Radar

If you routinely run at night, radar is closer to a must-have than a should-have. The same is true if fog is frequent on your home waters. And in much of the southeastern U.S., where summer afternoon thunderstorms are a fact of life, radar is important for safety because it allows you to thread your way home through the weather. Can you safely operate a boat at night, in fog or in thunderstorm-prone areas without radar? Of course, but radar makes all of the above both easier and safer.

Conical wood plugs

An inexpensive insurance policy, conical wooden plugs are used to plug broken below-waterline hoses, pipes, through-hulls, etc. They are normally sold in kits of five to 10 plugs of various sizes. If something breaks below the waterline, find the right size plug and hammer it into the broken pipe or fitting.

Throwable float with rope

Required Type IV throwable PFDs are better than nothing, but they’re not much good in rough conditions. First, once you throw one, you no longer have any control over its position. If your throw is inaccurate, it can simply blow away. Second, even if a person overboard is able to grab the cushion, you still have to maneuver the boat close to them to get them back aboard. Add a 50- to 100-foot length of floating rope, though, and you’ve got a much more effective MOB rescue device.

Even if your first throw is bad, you can use the boat to drag the flotation device to the MOB the same way you’d drag the handle of a tow rope to a down skier. Then, once the MOB has hold of the flotation device, you can use the rope to pull them by hand to the boat, rather than trying to maneuver close to them with engine power, which is very dangerous in anything but calm conditions.

A throwable flotation device with rope can be as simple as a regular Type IV cushion with 50 feet of floating poly line tied to one of the handles or as complicated as a Lifesling overboard rescue system.

Sea anchor

A sea anchor is essentially a small parachute that is deployed off the bow of your boat to dramatically slow your drift and keep your bow into the weather. If you lose power, deploying a sea anchor keeps you relatively stationary, making you easier for searchers to locate. And with your bow into the wind, you’re less likely to take water over the sides or stern.

Additional visual distress signals

The required complement of visual distress signals should be considered a bare minimum. Pyrotechnic devices — flares and smoke signals — are single-use; once you use them, they’re gone. Supplement them with longer-lasting devices like strobe lights, signal mirrors, distress flags and marking dye. Also consider adding more pyrotechnics.

Whistles and strobes on PFDs

This is verging on a “nice-to-have” item, but because of its affordability — assuming you don’t take a dozen people aboard — it makes this list. When a person goes overboard, whether or not they’re wearing a lifejacket is a critical factor in the outcome. But to increase survival chances even more, equip every PFD on board with a whistle and a strobe light to make MOBs easier to find for both you and potential rescuers.

Ditch bag

A ditch bag is a pre-packed bag meant to be taken with you in abandon-ship situations. What your ditch bag should contain is another discussion, but at the least it should contain distress signals, a waterproof radio, drinking water, a waterproof light source and a first aid kit.

Nice-to-Have Safety Boat Safety Equipment

The safety gear in this final category is certainly valuable but is needed by fewer boaters and in fewer situations than the equipment above. It tends to be valuable mostly for those who routinely make trips more than 20 miles offshore. It also tends to be relatively expensive.

Liferaft and/or survival suits

Liferafts are expensive and bulky but provide an obvious measure of safety if your boat sinks offshore.

Of course they help prevent drowning, but they also make it easier for crew to stay together in the water, and are much easier for rescuers to spot than a single person in the water.

In cold climates, survival suits are critical to delay hypothermia.

Backup GPS

If you’re far offshore and your primary GPS fails, you need a backup of some kind, even if it’s just a GPS receiver that shows your current position. Of course, if you’re boating far offshore, you should also have at least some proficiency in finding your way back home with a chart and compass.

Crew overboard devices

These small wireless communicators worn by crew members sense when someone goes overboard and trigger an alarm. A surprising number of people drown after falling overboard unnoticed while underway.

Crew PLBs

The next step beyond equipping crew with wireless overboard devices is outfitting them each with a PLB for easier location and rescue.

SOLAS-grade distress signals

Visual distress signals approved for use by SOLAS (the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea) are bigger, brighter and longer lasting than the standard USCG-approved signals.

For example, a USCG-approved handheld flare from popular manufacturer Orion produces about 700 candlepower.

The same company’s SOLAS-grade handheld produces 15,000 candlepower — more than 20 times the brightness. Of course, SOLAS-grade signals cost considerably more, but if you spend much time offshore, they’re probably a wise investment.

Satellite phone

Although not a replacement for an EPIRB, a satellite phone does have capabilities that an EPIRB doesn’t — namely two-way, real-time communication.

Final Word: It’s Not All About the Gear

Having plenty of safety gear aboard is great, but there are a few simple actions and procedures that can have just as much impact on your safety as the equipment. Here are two of the most important:

Have a backup operator

Unless you’re alone on the boat, you should always have at least one other person able to operate the boat and its systems in case something happens to you. Here are some basics that person should be able to do:

- Locate and use PFDs

- Turn on the engines, control the throttle and transmission, steer. All of this sounds simple, but is the person familiar with your kill switch setup? Do they know the engine has to be in neutral to start? Do they understand at least the basics of engine trim?

- Turn on the VHF radio, select channel 16, make an emergency call.

- Turn on the GPS, use it competently enough to get home, be able to find current coordinates and verbally communicate them via radio.

- Locate and activate any emergency beacons that aren’t automatically water-activated.

Practice using the MOB function on your plotter

Virtually all modern marine GPS/chartplotters have a prominent man-overboard key. When pressed, it creates a waypoint for the MOB location and triggers a series of other functions, which vary by manufacturer. If you’re serious about safety, practice using it by tossing a lifejacket overboard and then locating it. Of course, it’s easy in calm conditions, so practice with some wind and chop.